| Dak Lak, Gia Lai and Kon Tum provinces have adopted a policy on “conserving cultural values for tourism and economic development.” Wooden sculptures are now not only present silently in sacred graves in the Central Highlands, but also appear in public places and tourist sites. |

Bo ma is a festival where the architecture and folk art of sculpture of Central Highlands ethnic people originated and they are represented by statues on graves.

For Central Highlands people, a grave is not a monument, but a home for the dead, which must contain all the necessities needed in the other world.

Bo ma festival is regarded as the time for the living and the dead to part. After the festival, the dead are believed to go to the other world, bringing with them all the things that the living have made for or given to them in their home.

A grave in the Central Highlands includes a “house” and a surrounding fence. The house not only covers the underground grave and contains the things the living have given to the dead, but also serves as the frame where colorful, mysterious and vivid decorative sculptures and drawings are placed.

A Ba Na grave roof in Po Yang village, Kong Chro, Gia Lai province in 2009. Photo: Tran Phong

Artisans carve the statues on the grave. Photo: Tran Phong

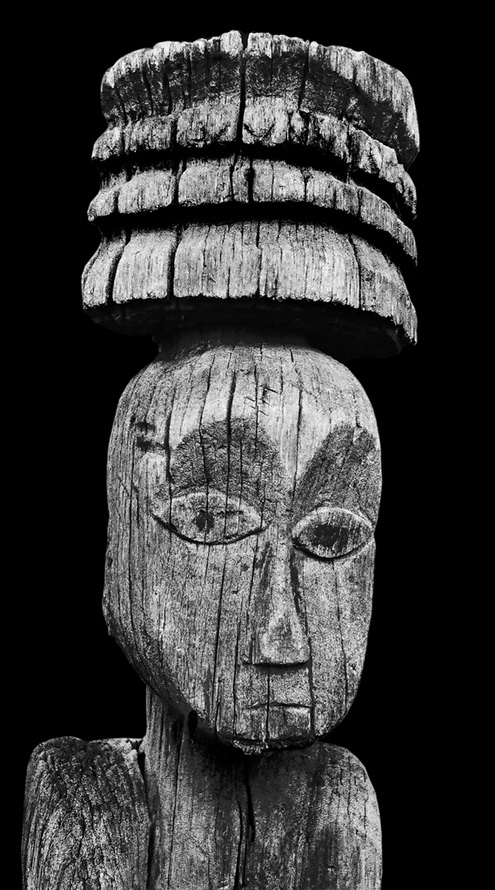

A sculptured face of the Gia Rai ethnic group in Cham village, la Grai district in 1986. Photo: Tran Phong

A statue of a Ba Na woman in Dak Gia village, Ya Hoi commune, Dak Po district in 1986. Photo: Tran Phong

The grave of the Ba Na in Bong village, Lo Ku commune, KBang district, Gia Lai province in 2015. Photo: Tran Phong

A statue of a Ba Na woman in Dak Gia village, Ya Hoi commune, Dak Po district, Gia Lai province in 2013. Photo: Tran Phong

A statue of a Ba Na woman in Bong village, Lo Ku commune, KBang district, Gia Lai province in 2004. Photo: Tran Phong  Statues of Ba Na men going hunting, Brul village, Cho Long commune, Kong Chro district, Gia Lai province in 1990. Photo: Tran Phong

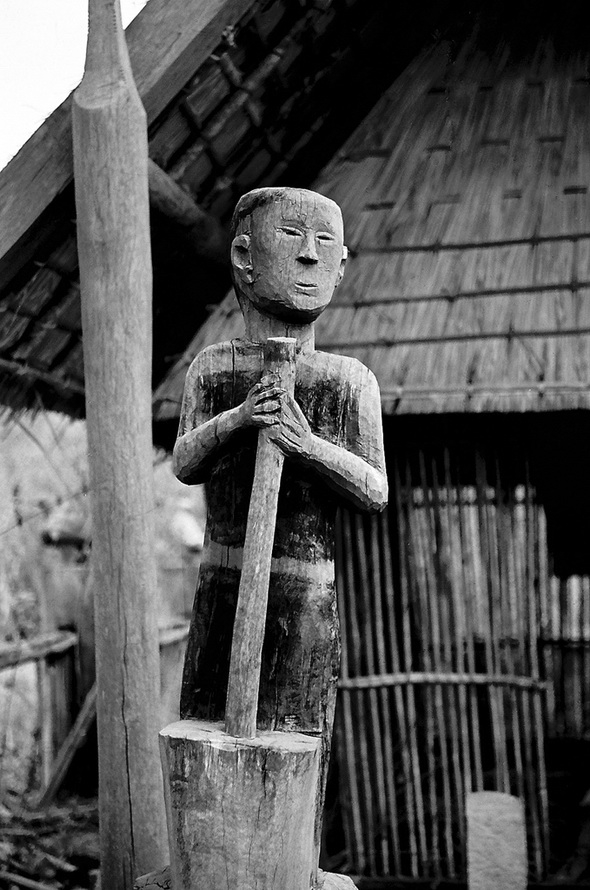

A statue of a Ba Na man pounding rice in De Nghe Kteh village, Kong Chro, Gia Lai province in 1986. Photo: Tran Phong

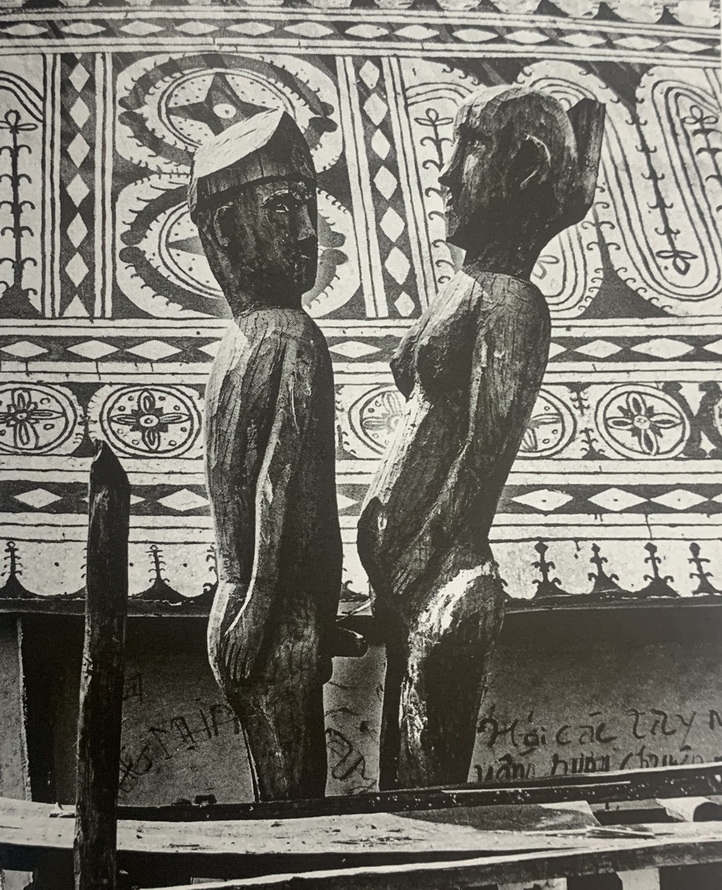

Statues of a Gia Rai couple sitting in front of a grave in Kepping village, la Mnong commune,

Chu Pah district, Gia Lai province in 2014. Photo: Tran Phong

A statue reflecting a man playing football, Gia Rai ethnic group, Phum hamlet,

la Rsiom commune, Krong Pa district, Gia Lai province in 1986. Photo: Tran Phong  A grave of the Gia Rai in Kepping village, la Mnong commune, Chu Pah district, Gia Lai province in 2006. Photo: Tran Phong A grave of the Gia Rai in Kepping village, la Mnong commune, Chu Pah district, Gia Lai province in 2006. Photo: Tran Phong |

The surrounding fence is not only for preventing wild animals entry but creates aesthetic values for the grave as well. The fence pillars are meditative but lively wooden statues which are imbued with the humanity and philosophy of ethnic people in the Central Highlands. It is also where unique folk sculptures are shaped.

Visiting graves in the Central Highlands, one seems to get lost in a maze of wooden statues in diverse shapes and expressions. But they all have one thing in common: the image of fertility, reproduction and growth. At the two sides of a grave is usually a pair of statues of a couple who either show their sex organs or are making love. Next to this pair of statues is the statue of a pregnant woman while in the four corners of the fence are statues of newborns.

|

“I, and the land and the age in which I am living in with a running cultural flow, pledge to be a “secretary” to record the developments of the art of wooden sculpture of the Central Highlands and act as a “hyphen” between the past and the future.” Photographic artist Tran Phong |

Having spent over 30 years photographing wooden sculptures in the Central Highlands, I regret that there are now not many chances to see artistic wooden statues which were popular in the past. Cement graves with corrugated iron roofs are replacing the ones with wooden structures. Old artisans have passed away, posing a threat for the disappearance of wood sculptures.

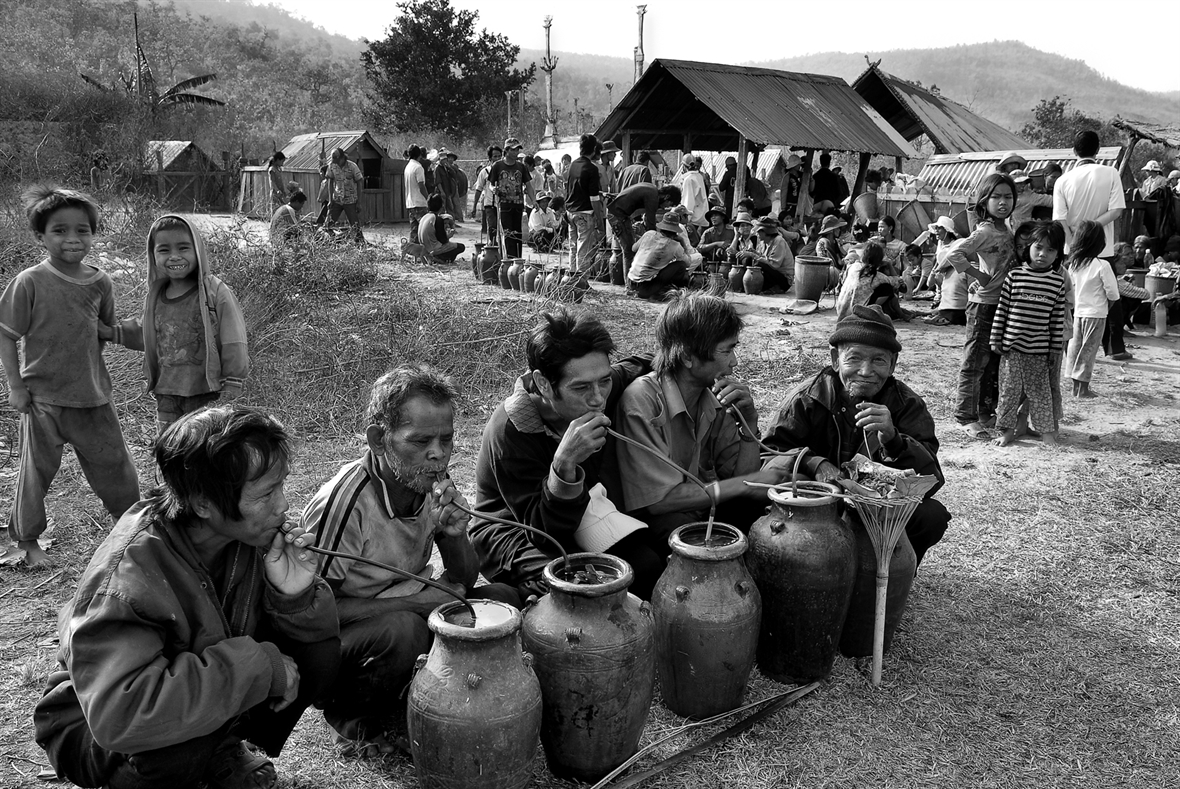

The grave area of the Ba Na ethnic group in Po Yang village, Kong Chro, Gia Lai province in 2015. Photo: Tran Phong  The Ba Na's bo ma festival in Lo Ku commune, KBang district, Gia Lai province i 2007. Photo: Tran Phong A bo ma ceremony of the Gia Rai in Kepping village, ia Mo Nong commune, Chu Pah district, Gia Lai province in 2004. Photo: Tran Phong  Drinking ruou can (a fermented rice wine that is drunk out of a jar through pipes) in a bo ma ceremony Drinking ruou can (a fermented rice wine that is drunk out of a jar through pipes) in a bo ma ceremonyof the Gia Rai in Chep village, Ayun commune, Chu Se district, Gia Lai province in 2011. |

Fortunately, when the art of wooden sculpture of the Central Highlands was beginning to vanish, the Party issued a resolution in July 1998 to build “an advanced culture deeply imbued with national identity”, which was a timely lifesaver for the art.

For the last decade, I was glad to see performances regarding carving wooden statues in major festivals in the Central Highlands such as the coffee festival and the gong festival in provinces such as Dak Lak, Gia Lai and Kon Tum.

The very few Ba Na, E De and Gia Rai artisans have also been invited to Hanoi to show the art of carving grave statues at the Cultural Village of Vietnamese Ethnic Groups and the Museum of Ethnology. In these places, Central Highlands wooden sculptures have been restored and introduced to the public. The statues also serve as a guide to lead tourists to the legendary wild Central Highlands.

.

| The book “Central Highlands Wooden Sculptures”, created by Tran Phong over a 30-year period, contain vivid and artistic images of the life and cultural formalities of the Central Highlands, many of which, however, have now been faded. |

By Tran Phong