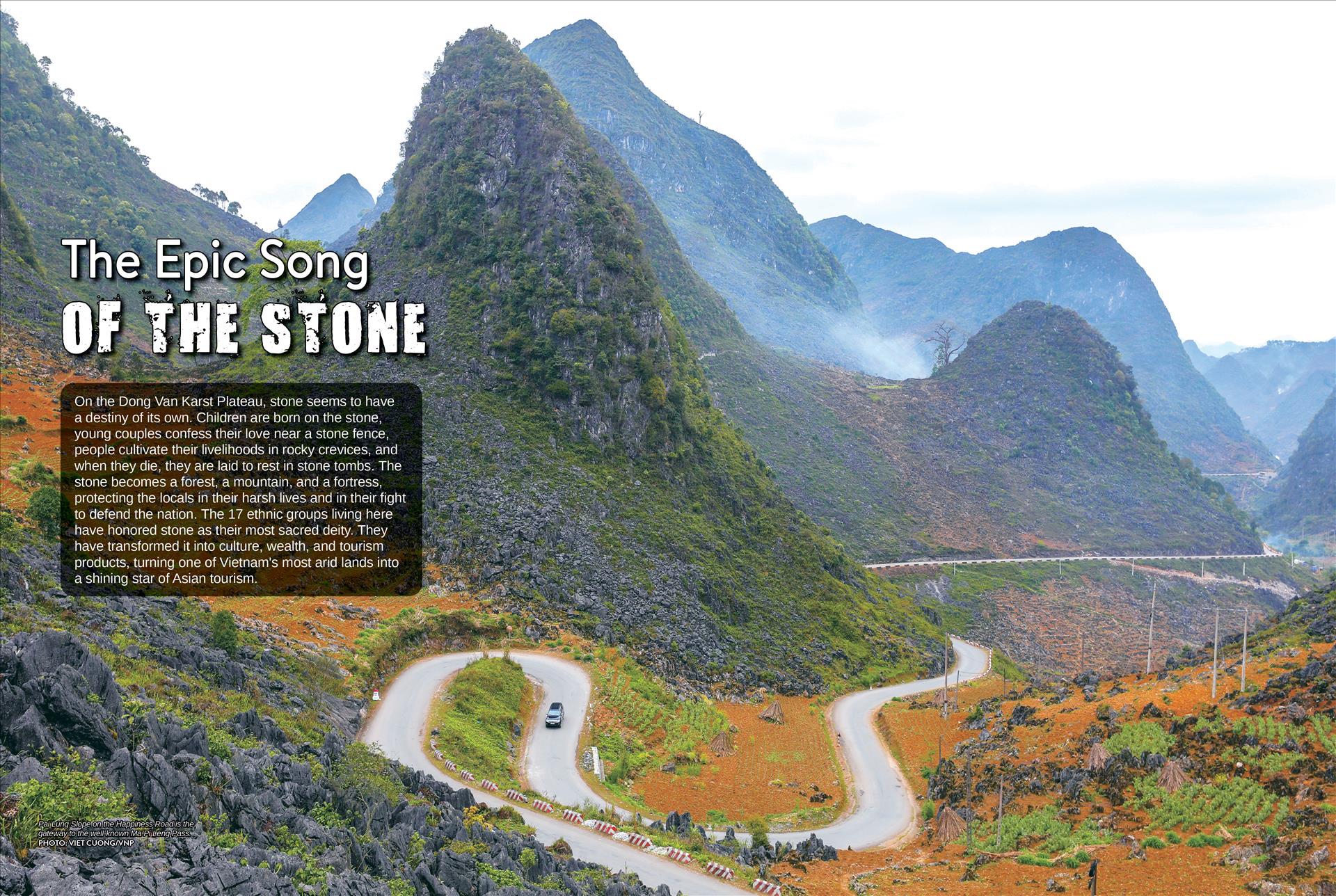

The Epic Song of the Stone

Fifteen years ago, intoxicated by corn wine I was talking with the "Stone God", Thao Mi Giang in Dong Van Commune. He told me about the people's stone beliefs. Thao Mi Giang is known as the "Stone God" by the H'mong in Dong Van because of his special talent for carving and shaping stone to build houses, create household items like mortars and pestles, and constructing the famous stone walls of Dong Van. He was the main character in the documentary film "The Song on the Peak of Ta Lung" by director Mac Van Chung, which won many major awards at national and international film festivals.

Giang recounted that the H'mong on the Dong Van Karst Plateau believe that in the beginning, the earth was just a soggy mass of mud. Two giant gods, the Tray couple, created stone, making the earth solid and firm. It was stones rubbing against each other that created fire, providing light and warmth and the ability to cook food for humans. It also brought forth corn, which later became the most important crop for the H'mong.

In Giang's stories, he spoke a lot about how the H'mong used the stone to survive. His ancestors taught him how to find the right stones to carve into mortars, pestles, doorsteps, and house pillars. "There's an endless amount of stone here," Giang said, "but not every slab can be made into a household item. You must find old stone, without any fractures or color impurities, to make it work".

According to Giang, every H'mong youth born before 1980 knows how to carve and shape stone. The younger generation carves stones into squares, rectangles, and circles to make bases for house pillars and doorsteps. The elders can chisel them into mills for grinding corn into flour or into decorative stone flowers.

Following Giang's directions, we found our way to the Chu clan in Sung Cang Hamlet to learn about their tradition of casting plowshares. The forge of Chu Dung Xiu, one of the three families of the Chu clan here, is red-hot all year round. In his halting Vietnamese, Xiu cheerfully explained, "We H'mong of the Chu clan use common cast iron, but with a special technique of using clay molds combined with our family's secret method, we create unique, sturdy plowshares that can cut through stone to till the soil for cultivation". As soon as a plowshare is finished, his wife and children take it to the Dong Van and Meo Vac markets to sell to the local H'mong.

The pinnacle of the 17 ethnic groups' use of stone on the Dong Van Karst Plateau is their technique of farming in rock crevices. Vang Mi Cho, another character from the documentary "The Song on the Peak of Ta Lung," said: "We H'mong, Tay, Nung and others have to build long stone walls around our fields, then carry soil from other places to fill them. In those fields, the soil clings to the rock crevices, and the stone walls hold the soil and water, allowing the corn and buckwheat to flourish".

If Thao Mi Giang is called the "Stone God," Dong Van also has Lau Then So, whom the H'mong call the "Fire God," and Vang Mi Cho, the "Water God". All three of these men helped break through the stone to build the 185km-long "Happiness Road" that runs along the Dong Van Karst Plateau. The road was completed in 1965. And these three outstanding sons of the H'mong, one with a missing arm, one with a missing leg, and one blind in one eye, all participated in the battle to protect the northern border in 1979, with the oath, "Live clinging to the stone, and when we die, we turn into stone to become immortal".

I returned to the Dong Van Karst Plateau in early 2025 and heard that the "Fire God" Lau Then So and the "Water God" Vang Mi Cho had returned to stone. The tombs of these two exemplary sons of the H'mong, also built from stone, stand proudly on the Ta Lung Mountain range. "That's how it is for the H'mong," the "Stone God" Thao Mi Giang said, his voice full of emotion. "When we die, we return to stone, saving the land so that corn, plums, peaches, and buckwheat can sprout, bloom, and bear fruit".

Creation seems to compensate for the hardships of human existence on the Dong Van Karst Plateau. While the region is dry from March to November, the spring months are adorned with a fairy-tale beauty of mustard flowers, buckwheat blossoms, plum blossoms, and peach blossoms.

Thao Mi Giang said, "About 300 years ago, the H'mong who migrated to this land, chose places where ancient peach and plum trees grew in forests to build their villages. The H'mong only brought seeds of corn, flax, buckwheat, and mustard to plant as food in the gray stone". Perhaps this is why wherever there are forests of peach and plum trees and fields of buckwheat and mustard flowers growing amidst the vast gray stone, that place is a H'mong village.

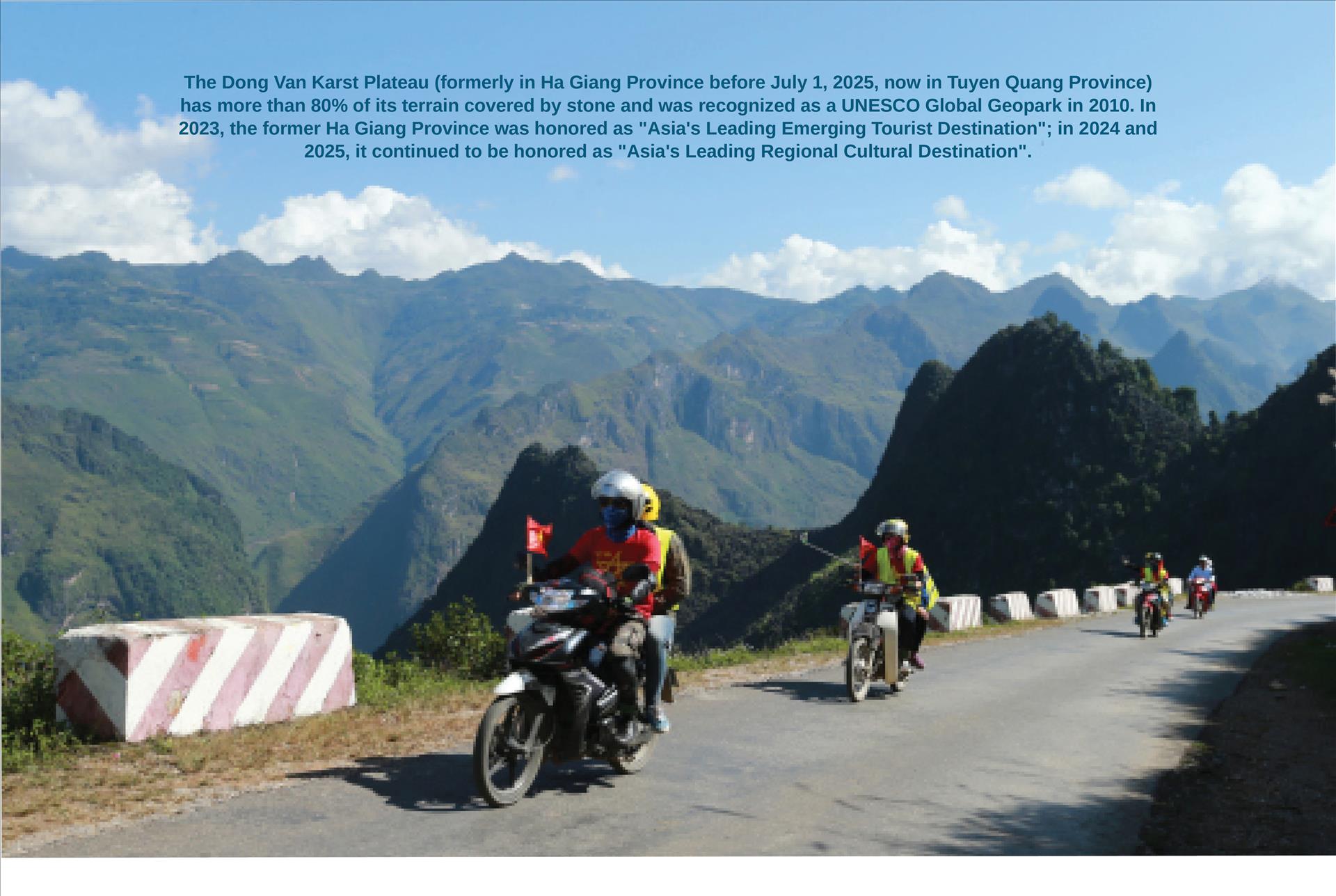

The unique stone structures - stone fences, stone patterns, stone tools - combined with the fairy-tale beauty of the blooming seasons, have attracted millions of domestic and international visitors to explore the Dong Van Karst Plateau.

For the past decade, photographer Tran Cao Bao Long from Ho Chi Minh City has traveled more than 2,000km to the Karst Plateau every spring, staying for months at a time to capture the wonderful moments of life. "I live with a H'mong family in Lung Cam, and I've become one of their family members. This family runs a homestay called Moc. Moc is special compared to other tourist villages because of its quiet, rustic decor and the hosts' generous hearts".

The walls of the Moc homestay are adorned with impressive photographs: images of golden mustard fields, ancient peach trees showing off their blossoms in the morning sun, and portraits of the people who "live on the stone". These are photos gifted by photographers who have stayed here. "I took this photo of the golden mustard field last spring. Now I have a large print made for the family, so that every time I return to Moc, I feel like I am coming home," photographer Tran Cao Bao Long revealed.

Dong Van does not just attract tourists and photographers; it has also become a giant film set for Vietnamese directors to unleash their creativity on the stone. With the spirit of "cinema leading tourism," cinematic works like "Pao's Story," "Silence in the Deep," "Red Sky," and "Tet in the Village of Hell" have brought the karst plateau closer to both domestic and international visitors.

Beyond film and photography, domestic and foreign literary circles have also been impressed by Thuy Tran's travelogue "Missing Dong Van". Dong Van is not just about cat-ear stones, rammed-earth houses, winding roads, and deep gorges, it also has highland markets. Thuy Tran suggests that when you come to Dong Van, you must take the time to visit a market, to lose yourself in the sound of the leaf harmonica, to sit by a steaming pot of "thang co" (a traditional stew), drink a bowl of corn wine, and smoke a pipe of tobacco to warm your stomach. And the Dong Van stone market still stands, preserved as a testament to the extraordinary rise of the people of this stone region.

As for the "Stone God" Thao Mi Giang, a man who is nearly 92 years old and has lived through all the joys and sorrows of this karst plateau, feels content now that his homeland has become the "tourism capital of the Northeast". Looking at the distant, hazy Ta Lung Mountain range, he softly recited a H'mong proverb: "No mountain is higher than a H'mong person's knee," to speak of his people's heroic determination to live with and use the stone./.

Story: Thong Thien Photos: VNP Translated by Hong Hanh

- Designed by Trang Nhung