Reclaiming the Soul of the Mekong’s Floating Markets

But when she realized we were just tourists taking photos, Hau sighed, “What's left of the bustling floating market scene for you to photograph, dear? People have all moved to the markets on land". In the dim light, her husband Nguyen Van Hung was already awake. Hearing our conversation, he joined in. “About ten years ago, we lived in Long My,” he recalled. “Every month, we’d head to market four times. Each trip, we loaded up four or five tons of fruit on our boat, traveled up the Xang Canal, and in four or five days, we’d sell it all at the Nga Nam and Nga Bay floating markets”.

Back then, Hung said, the entire Long My District buzzed with people preparing for market trips. Even poor families would scrape together enough to buy a small boat with a motor so they could sell pineapples and pick up household goods to bring home. Now, his is the only boat from Long My District still anchored at Nga Nam.

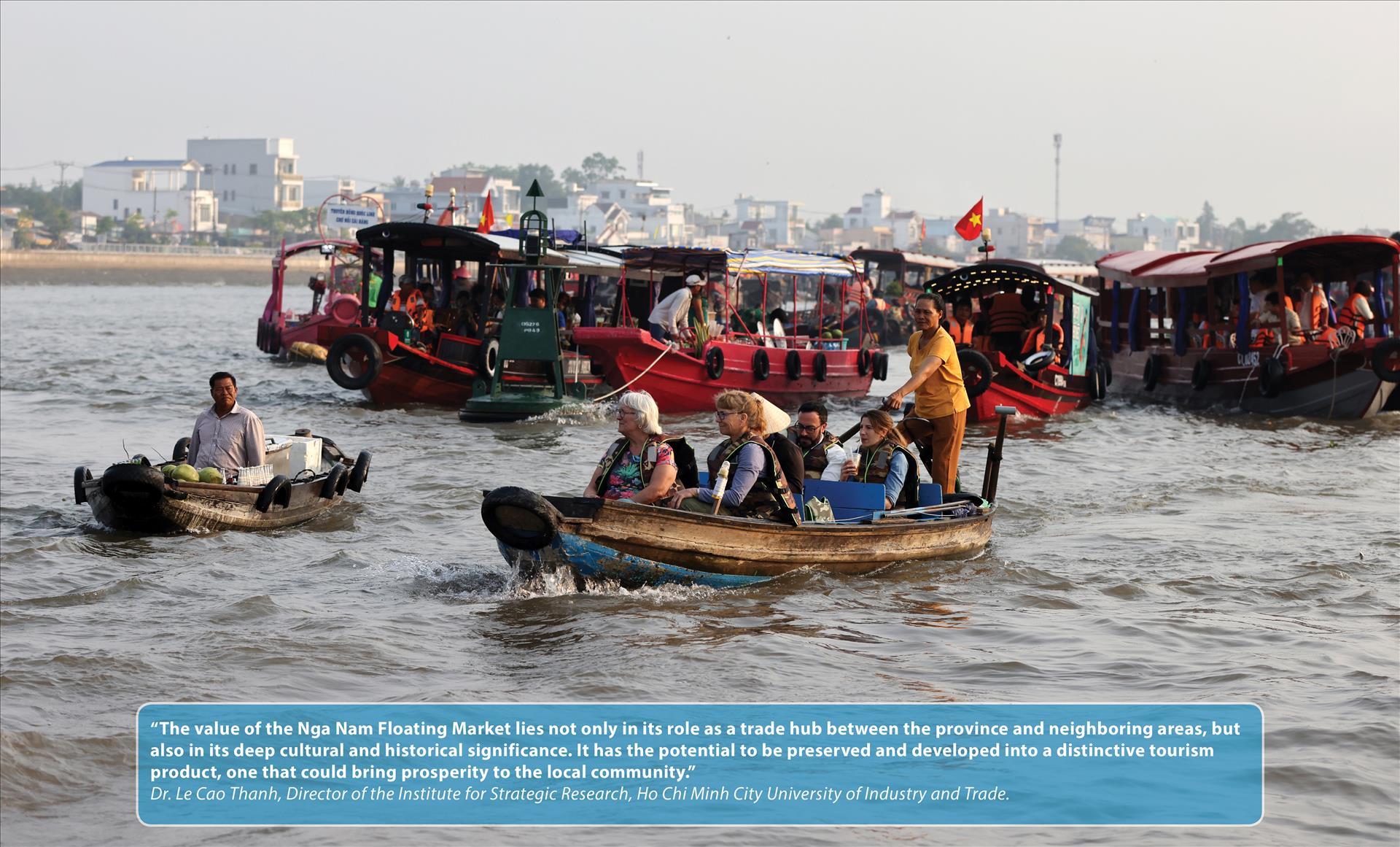

Alongside Hau’s pineapple boat, at the confluence where five rivers split off toward Ca Mau, Vinh Quoi, Long My, Thanh Tri, and Phung Hiep, only about a dozen other boats from other districts remained, selling watermelons, pineapples, and coconuts.

Docked nearby was Le Van Dinh’s watermelon boat. Dinh traveled from Vinh Quoi and anchored there three days earlier. That morning, only two restaurants had stopped by to buy a few dozen watermelons for their customers. After selling what little he could to a few passersby, Dinh brewed tea and invited us aboard.

Letting out a weary sigh, he said, “Think about it, guys. Now that the roads are better, with motorbikes and cars everywhere, people just go to land markets. Traders head straight into the orchards to buy. Nobody bothers with floating markets anymore. And besides, there’s no real flood season in the Mekong Delta these days. Without high water, boats can’t get around easily. Who would bother with a floating market now?”

At Nga Nam, aside from Hung and Dinh, only about a dozen merchants remained, clinging to this vanishing way of life. As Hung put it, “We don’t make much money anymore. But we’ve spent our whole lives on these rivers, living on boats. It’s what we know. When we’re gone, I doubt the younger ones will even know what a floating market is”.

We continued up the Xang Sa No Canal to Nga Bay Floating Market in Hau Giang Province. According to local officials, Nga Bay, also known as Phung Hiep Floating Market, has a history stretching back more than a century. Established around 1915, it sat at the junction of seven rivers: the Cai Con, Mang Ca, Bung Tau, Soc Trang, Xeo Mon, Lai Hieu, and Xeo Vong. It was once the Mekong Delta’s busiest trading hub.

But from a drone’s view, the intersection where those seven rivers met now showed only scattered boats passing by, with houses lining both banks. There was no trace of the bustling floating market it once was.

We stopped at a roadside tea stall and asked the woman running it about the market. She gave a brief, resigned reply: “Before COVID, the market still gathered right there. But since then, no one’s come back”.

We traveled to Can Tho, known as the land of "white rice and clear water," and made our way to Ninh Kieu Wharf, where boats take visitors to explore the Cai Rang Floating Market. A boat owner there told us that while the market still exists, it is no longer busy with boats the way it once was, because the soul of the floating market - the traders – has dwindled.

Looking around, we saw only about 20 large boats left selling agricultural produce. Dang Van Nam, one of the remaining boat traders, explained that most of the boats here now sell long-lasting goods like gourds, pumpkins, and coconuts, while smaller boats roam the market selling fruit to tourists.

We stopped by the boat of Nguyen Thi Kim Chuong, who sells drinks at the Cai Rang Floating Market. Chuong told us that while the market used to be full with boats trading farm produce, those have mostly been replaced by boats catering to tourists. These days, her boat sells a few dozen cups of coffee, tea, and soy milk to visitors each day, not much, but just enough to get by.

“If we can properly organize the floating market, preserving the active trade among boat merchants while integrating tourism and cultural activities, its value will remain intact and might even grow,” suggested Dr. Tran Huu Hiep, Vice Chairman of the Mekong Delta Tourism Association.

Story: Thong Thien

Photos: Nguyen Thang, Le Minh & Thong Thien/VNP

Translated by Nguyen Tuoi